Your lender and your auctioneer may be the same person. Does that change your risk?

Auction houses don’t just sell art anymore, they finance it. Sotheby’s and Christie’s now run full-scale lending desks that will advance a percentage of the low auction estimate against your work, sometimes as a straight term loan, sometimes as an “advance” tied to a planned sale. The pitch is speed, discretion, and in-house expertise. The catch is structural: when the same institution values, lends against, and can later sell your collateral, incentives braid together in ways that can tilt your effective LTV, your fee stack, and your exit options.

Here’s how the mechanics create that tilt. First, both houses openly base loan size on the low estimate set by their own specialists. Sotheby’s says it “generally” lends 40–60% of the low estimate and, while it stresses that most loans don’t require a sale, it also offers short-term advances against consignments, explicitly linking finance to selling.¹ Christie’s mirrors the model and even advertises “more advantageous terms” for loans structured as advances against sale.² That’s a clean articulation of the dual role: the loan can be the bridge to a consignment the same company will monetise.

Second, the sales side increasingly runs on guarantees and irrevocable bids, financial instruments that shift risk away from the house. In May 2025 New York evening sales, 73% of hammer value rode on third-party guarantees, according to Pi-eX data reported by Observer.³ That risk engineering is rational for the house, but it complicates borrower incentives: if your lender/auctioneer can place a guarantee (and sometimes finance the guarantor), it may prefer a sale path that optimises the house’s fee and risk, not your upside. Sotheby’s acknowledges that irrevocable bidders may receive financing related to their bids, confirming that multiple economic roles can sit inside the same deal.⁴

Third, auction lenders themselves now tap public capital markets. Sotheby’s packaged $700m of art-backed loans into rated securities in 2024 (upsized from an initial $500m), boosting its total lending capacity to $2bn, according to Financial Times reporting.⁵ Securitisation rewards conservative collateral marks, quick recoveries, and low loss severity. If your lender/auctioneer is also an ABS issuer, the portfolio’s performance targets can nudge underwriting, margin-call behaviour, and sale timing in ways you’ll feel when markets wobble. In early 2025, the FT also reported that art lenders, including the big houses, had issued margin calls as prices softened, forcing borrowers to add collateral or sell.⁶

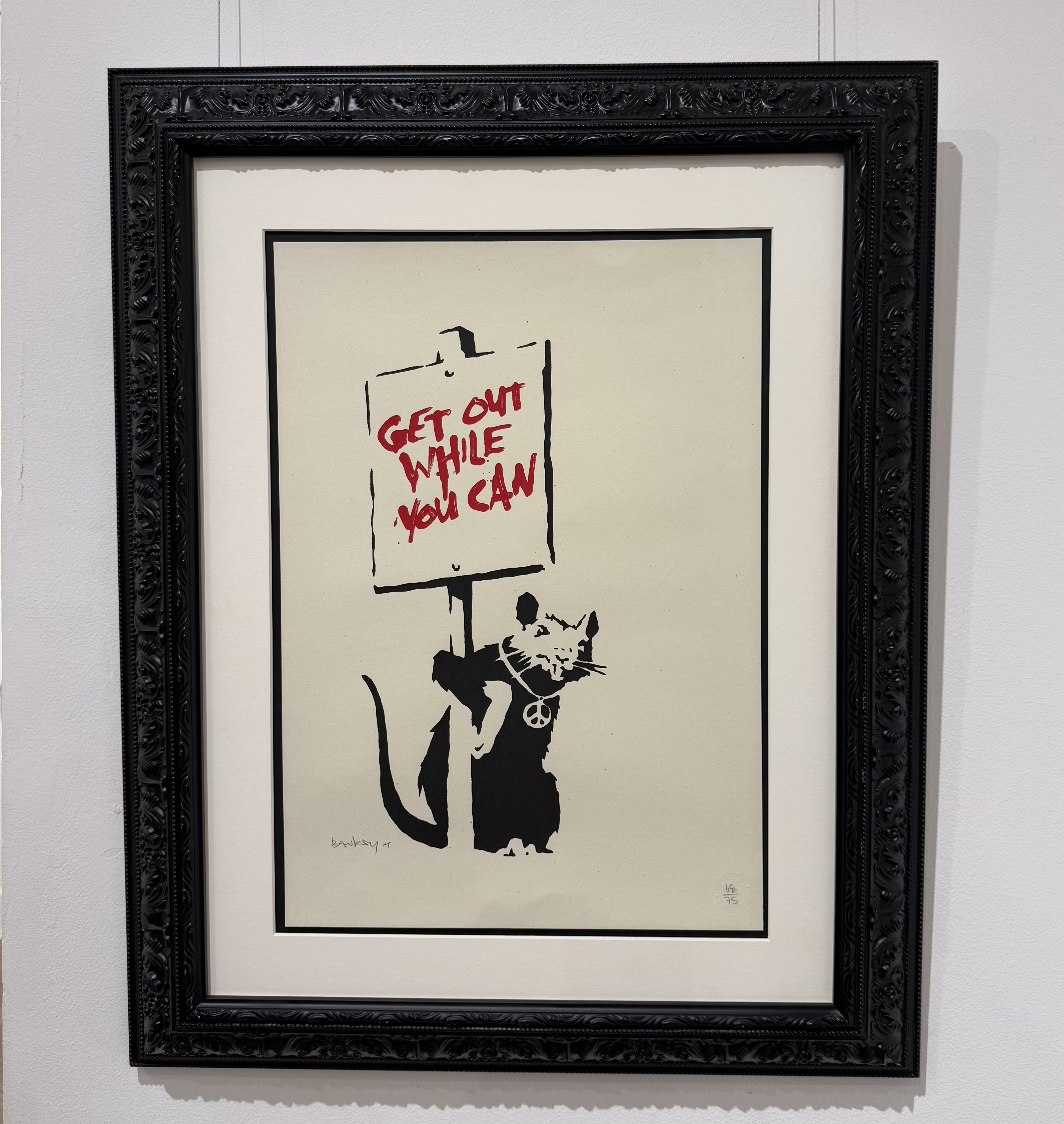

Banksy, Get Out While You Can [Red] (2004), Artscapy. Photo: © Rhea Mathur, ICONS exhibition at the Marie Jose Gallery, 2025.

Zoom out and the macro only tightens the knot. The 2025 Art Basel & UBS report pegged 2024 global art sales at $57.5bn, down 12% year-on-year.⁷ Meanwhile, Deloitte’s Art & Finance Report estimated $29–34bn of outstanding art-secured loans in 2023 and projected growth toward $40bn by 2025.⁸ More leverage, softer top-end prices, and auction houses wearing multiple hats is exactly the backdrop where dual-role conflicts have teeth.

To be fair, the houses do acknowledge the potential for conflicts and bake in disclosures. Sotheby’s Financial Services states that two-thirds of its loans are term loans with no commitment to sell, which matters because many clients do borrow without a sale plan. Christie’s conditions of business highlight that there is “no obligation to sell” when financing is provided, though more advantageous terms may apply if the borrower does. These points don’t erase the conflict, they just make it knowable for a sophisticated borrower.

Where the rubber meets the road is negotiation. If the same brand is setting your low estimate (thus your LTV), writing your loan, proposing your guarantee, and (if needed) running your sale then your effective LTV isn’t just a number on a term sheet. It’s the outcome of a system optimised for the house’s credit quality and fee capture. In a quiet market, that can manifest as: lower starting estimates, stricter advance rates, faster triggers to convert from term loan to consignment, guarantee options that monetise certainty for the house while capping your upside and if loans are securitised, portfolio-driven conservatism around recoveries. None of this is nefarious - all of it is predictable once you trace the money.

What’s the perfect play if you want liquidity and control?

Compare to a pure-play lender. Private banks and specialty art-finance lenders, such as Artscapy Finance, can’t auction your work, by design. That single-role model matters. Independent firms don’t set your auction estimates, don’t have a financial interest in pushing a consignment, and don’t package loans into ABS portfolios that reward ultra-conservative marks. The incentives are cleaner: to lend prudently, be repaid, and preserve the borrower’s flexibility. The benefits can include:

- Neutral valuations. Many independents rely on third-party appraisals or multiple opinions, which can mean a higher advance base.

- Flexible structures. Unlike auction desks tied to consignment calendars, independents can structure multi-year facilities, revolving lines, or bespoke repayment profiles.

- Global storage optionality. Loans are often secured with works held at approved third-party warehouses, not restricted to a single auction house facility.

- Discreet relationship lending. No need to telegraph to the market that a work is “in play” just to secure liquidity.

- Control at exit. If you decide to sell, you choose when, where, and how – auction, private, or not at all.

If you do stick with an auction-house loan, here are the precautions:

- Decouple valuation from lending. Push for an independent valuation (or dual appraisals) instead of relying solely on the house’s low estimate. Even a modestly higher base can add real dollars at 50% LTV.

- Hard-separate loan and sale. If you don’t plan to sell, strip cross-defaults and pre-agreed consignment rights out of the loan docs.

- Interrogate the guarantee. Ask who’s putting up the irrevocable bid, whether they’re financed by the house, and how upside and fees split.

- Plan for volatility. If prices slip, margin-call math moves quickly. Model a 10–20% drawdown against your LTV and decide now how you would respond.

Bottom line: auction-house credit is fast, expert, and sometimes cheaper. But the dual role is real. If the lender can also consign and sell your collateral, you’re not just negotiating a rate, you’re negotiating who controls the levers (estimate → LTV → guarantee → sale). Lock down independence where it counts and you keep the math working for you, not just for the machine surrounding your art.

Photo: © Rhea Mathur, New Geographies exhibition at the TAGLI, 2025.

Footnotes